Young professionals, sparing no time, talent, or money, seek to prove that Lithuania can proudly participate in space exploration along with the United States, Russia, China, or India.

Joke turned reality

“There's an established stereotype that Lithuania is an underdog, that it is too poor and too weak to do anything in space exploration. We want to bust this myth,” Laurynas Mačiulis, one of the creators of the Lithuanian space satellite Kosmis, told 15min.

Almost two years ago, Lithuania was visited by a delegation from the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) that suggested building a Lithuanian satellite. “NASA representative made a joke that we should outrun Latvians who were already working on their satellite,” recalls one of the founders of the Kosmis project, Vytenis Buzas.

He has been interested in technology, especially engines, since childhood, when he started collecting engineering blueprints that he would study thoroughly.

“When I learned about a possibility to build a Lithuanian satellite, I had no doubt whatsoever that, with a little effort, it was possible. That was an excellent opportunity to use my knowledge. Ever since that day, I would wake up and go to sleep thinking about a Lithuanian satellite,” he says.

But it was hard work ahead – engineers were developing the satellite concept and working out a technology for it. The task was quite a challenge due to lack of experience in similar projects, so the team had to bring in foreign specialists for help.

“At the moment, the satellite project meets strict standards, so we can confidently proceed to the next stage,” the satellite builders say.

Off to space in 2015

Mačiulis makes no secret of the fact that his main objective in this project is to inspire Lithuanian youths to take interest in space technology. Even if the launch fails, the project will still have achieved its educational goals.

The satellite builders hope that their research will not go to waste and will become a cornerstone of a scientific database which is currently developed by Vilnius University, Kaunas University of Technology, the Lithuanian Energy Institute, and several private companies.

“Our curiosity leads us forward. Perhaps in the future, we will create an international business to help us satisfy this engineering curiosity. We want our project to be made in Lithuania,” Buzas grins, recalling all the offers for the young engineers to go and work abroad.

Meanwhile the satellite project is nearing completion. According to plans, Kosmis should be launched into space in mid 2015.

“We are taking part in a programme of the Brussels-based von Karman Institute, QB50, which envisages launching 50 small satellites from different countries,” the Lithuanian engineers say.

Investing own money

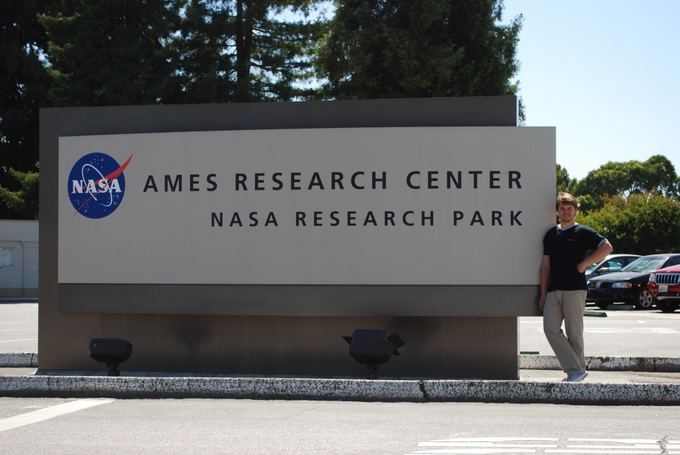

The young engineers currently intern at NASA Ames research centre to improve their knowledge. The Lithuanian project was introduced to colleagues at the research centre and received much support. Russians, too, showed interest in the project.

However, the biggest obstacle that the Lithuanian engineers still need to overcome is lack of funding. Until now, they have been investing their own money into the project that could become the start of Lithuanian space infrastructure.

“Lack of funding is no excuse. That is a creator's responsibility, since he is the one who must prove to others that the idea is useful and worthy of investment. We go by this principle and look for funding sources in both private and public sector,” Mačiulis says.

“We receive much support from the international community. It is tough at times, but no one said it would be easy. When we started on this quest, we knew what we were getting into. Only those who lack confidence or know not what they're doing complain.”

|

| Asmeninio achyvo nuotr./Vytenis Buzas |

International project

The network of small satellites – the so-called CubeSats – will serve in a long-term research of the lower thermosphere and ionosphere.

Circling the Earth in lower orbits, the small satellites will be descending into lower layers of the thermosphere due to air resistance, measuring physical parameters across space. Average orbit-life of these satellites should be 3 months.

The mission is unique in that, for the first time, so many nanosatellites, built by students of various universities throughout the world, will form one network in space.

Until now, up to 100 universities applied to take part in the QB50 project, but only 50 satellites will have a place in the rocket.