Shrinking space

It has been a tough journey for civil society in Uganda, where over the last few decades it has mutated from predominantly service-delivery to advocacy on human rights, governance, and accountability issues. The shift started occurring in the mid-1990s, following the realization that the way non-governmental organizations (NGOs) had been approaching development achieved limited results. “Their work was likened to patching up wounds without addressing the root causes of the problem,” – notes Chris Nkwatsibwe, Coordinator for Civic Space and Governance Monitoring at the Uganda National NGO Forum, an umbrella organization with more than 650 member NGOs across the country. Hence the need to shift major focus to balancing out the relationship between the people and the state – in order words, for the civil society sector to become more of a government watchdog than a provider of public services that the government itself was set up to provide. The period also witnessed a high increase in the number of organizations: in 1988, Uganda had 94 registered NGOs; in 2016 there were around 13,000.

But the shift in NGO focus from service delivery to advocacy not only had a significant effect on the nature of the relationship between NGOs and the state; it also came with a cost – to the NGOs themselves. While the Ugandan government welcomes the social services many civil society organizations (CSOs) provide, at the same time it feels threatened by the possibility of political mobilization and empowerment of the population that come with self-organized practices; needless to say, such threats to the government’s grip on power yield conflicts between the state and civil society actors. In response, the state has introduced various ways of limiting people’s freedoms and putting legal obstacles for civil society organizations and individuals, such as the infamous NGO Act of 2016.

The operating environment and the restrictive NGO laws have meant that NGOs have to navigate a thin line between survival and implementing their activities,” – says Nkwatsibwe. Moreover, the continued retrogression of the state in terms of its democratic credentials has also impacted CSOs variously. Organizations that engage in monitoring the state’s conduct and advocate for human rights, anti-corruption, accountability, and democratic governance have experienced growing restrictions on the space available for them to carry out their activities. One of the most recent examples is the Uganda Communications Commission Guidelines for everyone posting content online, including bloggers and online news platforms, which aim to control people’s freedom of speech.

However, despite various restrictions, civil society organizations in Uganda are still seeking – and finding – ways to try to expand space for their operations. One of these is to build organizational capacities by providing training and funding opportunities. A case in point is FABIO – the First African Bicycle Initiative Organization, which promotes sustainable transport solutions for vulnerable communities, particularly in Uganda’s Busoga sub-region. As members of the Uganda National NGO Platform, people at FABIO received training in local resource mobilization strategies which contributed to their growing their bicycle centre to increase their locally-generated income.

Centralizing funding

The CSO situation on the North-Eastern edges of the European continent is rather different, but not completely so. There, too, a balance in the relationship between the people and the state is needed. “There is currently a lack of sustainable mechanisms in place to help strengthen the capacity of NGOs to participate in decision-making, advocacy and policy processes,” – says Justina Kaluinaitė, Policy, Advocacy and Partnership Officer at the Lithuanian National Platform of Non-Governmental Development Cooperation Organizations (Lithuanian NGDO Platform), an umbrella organization with 21 member NGOs working in the field of development cooperation. She hopes that the establishment of the Fund will provide a mechanism that would enable the strengthening of such capacities.

The NGO Fund was set up by law in Lithuania in 2020. It is expected to carry out regular monitoring of the developments regarding public participation in public policy and decision-making processes. For many years, NGO projects in Lithuania have been funded from the state budget. “The new instrument places a focus on strengthening civic society through the development of non-governmental organizations’ databases and funding schemes, – explains Kaluinaitė. – The development of the NGO database and more specific regulations defining the “non-for-profit” may help create a clearer way to provide information on whether a legal established body is an NGO aiming to address social needs or just registered as NGO but could be oriented to business actions or government-organized non-governmental organizations.” The projected NGO Fund is expected to have a specific annual budget, approx. 2 million euros, but it is not yet clear how this money would be allocated.

Meanwhile, Lithuanian CSOs are continuing their activities in various fields. Over the last year there have been various initiatives aimed at easing the isolation of vulnerable people, particularly the elderly, during the country-wide lockdown, and providing them with food supplies and basic human contact. While some local actions were undertaken by grassroots volunteers, well-established CSOs have also continued their efforts, as in the case of the Maltesers and their soup – a hot nutritious dish that is being delivered to elderly people who live alone and often face the double-challenge of loneliness and poverty. Meanwhile, other NGOs are engaging in development cooperation projects, varying from developing renewable energy resources in Moldova (Green Policy Institute) to ICT skills enhancement between Lithuania and Nigeria (Afriko).

A global view

Both the Uganda National NGO Forum and the Lithuanian NGDO Platform are members of FORUS, a global network of 69 National NGO Platforms and 7 Regional Coalitions from 5 continents. Here, FORUS Director Sarah Strack and Advocacy Coordinator Deirdre de Burca share their perspectives on the current shape and challenges facing civil society organisations (CSOs) across the globe.

How successful, in general, do you think CSOs have been in their function as a watchdog, and ensuring that their work always has the people's best interests at heart? What obstacles might prevent or slow down this process and how are they being / should be tackled?

CSOs have played an extremely important role as a public watchdog in recent decades, holding governments to account for commitments they have made at national and international levels. One only has to think of the 2030 Agenda or the Paris Climate Agreement or various international human rights treaties to realise that without civil society pushing governments to account for the commitments they made, the agreements themselves wouldn’t be worth the paper that they are written on. There is still a long way to go for governments to walk the talk. We need to see more binding commitments and find ways for people to also share their lived experiences about the way in which their governments put in place the enabling environment for the full realization of their promises. CSO networks play a particular role in this regard, as they can amplify people’s voices and convene a diversity of constituencies that act in the public interest.

But CSOs are in many instances limited in terms of human resources, expertise, funding etc and cannot always perform the role of watchdog as effectively as they would like. There is also sometimes limited engagement of CSOs at the grassroots. CSOs must continue to improve in better reflecting the needs from the local and communities level into their advocacy and in channelling the voices and demands of people into the decision-making arenas.

In terms of good governance, how would you describe a healthy relationship between a government and the NGO sector? Who should be accountable to whom and how can that be implemented? Do we have good examples of this? Additionally, how are CSOs coping under especially repressive government regimes and what do they actually achieve under such circumstances?

A healthy relationship between a government and the NGO sector is one which is based on mutual respect and meaningful engagement. This is why regular and structured dialogue between CSOs and different parts of government are so important – so that there is space for constructive debate. There should be accountability on both sides – government should be accountable to civil society and the public at large for acting on commitments that it has made. CSOs need to be accountable to their constituency in order to be legitimate, effective and efficient in the use of its funds, act in line with their values and objectives.

However, it is very difficult for CSOs to hold governments to account in contexts where the government sees civil society as having little legitimacy and where it refuses to engage with them. The shift towards greater authoritarianism and the shrinking civic space in different regions of the world means that Forus members are increasingly finding it difficult to hold their governments to account. CSOs in countries such as Brazil, India, Chad, and Zambia, amongst others, report considerable difficulties to fulfil their missions because of a variety of challenges such as restrictions on fundamental freedoms, restrictive regulatory environments or intimidations or attacks of activists.

What steps are being taken to expand the shrinking civil space? What steps aren't being taken, but should be?

CSOs are working to expand civic space, through working in coalitions, including with other sectors and allies with which they share the same values. We also see innovative initiatives to mobilize against restrictions to civic freedoms, for example through online organizing or through partnerships with engaged media that are using storytelling approaches to share the stories of those affected.

But much more can and must be done. We need bolder and continuous commitments from progressive allies to support civil society and activists in places where civic space is under threat. Both through rapid response mechanisms in the case of immediate threats, as well as through long-term support to strengthen the networks, groups and mechanisms that exist on the ground to be able to push back against these trends, to organize, and to implement durable responses and solutions.

Do you also see this trend of finances being reduced for NGOs globally? If so, what are the factors driving this and what are potential consequences for civil society, funding being one of their primary concerns?

The general trend of decreasing funding is worrying, especially as we see some champion countries, such as the UK, further reduce their development aid budget. As part of this trend, the challenge of securing sustainable and predictable funding for CSOs is a major concern, which has prompted Forus to make this part of its core advocacy messages. The current Covid19 pandemic is only exacerbating this concern and risks to further affect CSOs’ ability to operate. To some, the fragmentation of the CSO space is one explanation of the general trend; to others, the more political dimension (as opposed to service-delivery role) that some CSOs adopt is seen as a factor. A third reason is the hunt for ever–more “value for money” which many donors adopt. While the drive for strengthened accountability and effectiveness is welcome and important, the interpretation of the value for money concept sometimes poses problems. We need much more qualitative indicators to ensure that the coordination, capacity–development, alliance–building and community–engagement work of CSOs is adequately valued and supported.

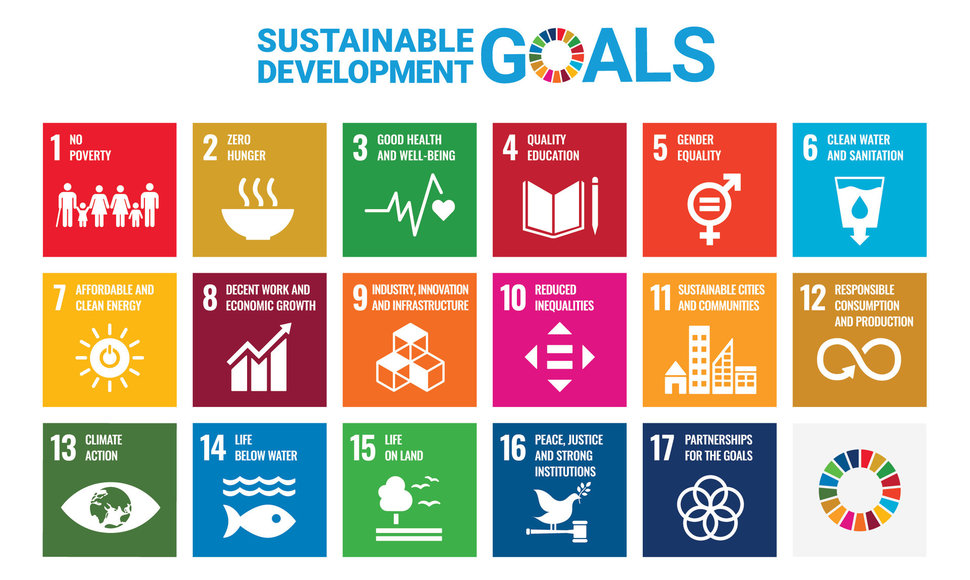

In 2019, Forus published a study on “Innovative Approaches to CSO Funding” in which members were consulted about the kind of funding mechanisms that would best support the work of CSO platforms and networks, and showing the critical need to be able to better adapt to demands and particularities of the different contexts that CSOs operate in. In addition, a global financing system to ensure that CSOs have access to funds to support their strengthening is a key ask of the network in the context of the operationalization of SDG 17.

How can the CSO sector gain more trust and confidence from the general public in places where it’s lacking?

Civil society needs to embrace and socialize much more positive, evidence–based, solutions–oriented and hope–filled public narratives, better explaining the many roles it fills and the added public value it provides, and better amplifying voices from the ground. Civil society also needs to continue to strengthen its own transparency and accountability so that it makes itself more open to public scrutiny and lives up to the standards that it is demanding of other actors.

How would a perfect CSO–enabling environment look like, in your vision?

An environment enabling civil society to thrive is made up of many different elements. Some of the main elements are (i) the protection by government of the fundamental rights including the right to freedom of assembly, association and expression (ii) an enabling digital, legal and regulatory environment for CSOs (iii) inclusive governance including good access for CSOs to policy and decision-making spaces at every level (iv) a positive public narrative about civil society that is shared and promoted by government (v) adequate, sustainable and predictable funding for CSOs (vi) access to ongoing opportunities for CSOs’ capacity–development.

A publication titled “CSO space and the role of national platforms in policy and practise: Lithuania and Uganda” is being published by the Lithuanian NGDO Platform together with the Uganda National NGO Forum. It can be accessed online at https://issuu.com/vbadmin/docs/lithuania_and_uganda_csos_forus