Hiding from cold

According to contemporaries, the 1917-1918 winter was exceptionally frosty, with shortage of firewood and severe cold making people freeze to death. As the story goes, Jonas Basanavičius himself had nothing to put in his hearth. Therefore, twenty members of the Council of Lithuania, eager to proclaim their motherland independent, assembled in a much wormer house in Didžioji str. In Vilnius (now Signatories' House 26 Pilies str.), owned by Kazimieras Štralis, in the office of Antanas Smetona, who was then chairman of Lithuanians' Society for Supporting War Victims.

Even though the Society was merely a charity organization, during the war it turned into political rallying point and later provided funds for the Council of Lithuania.

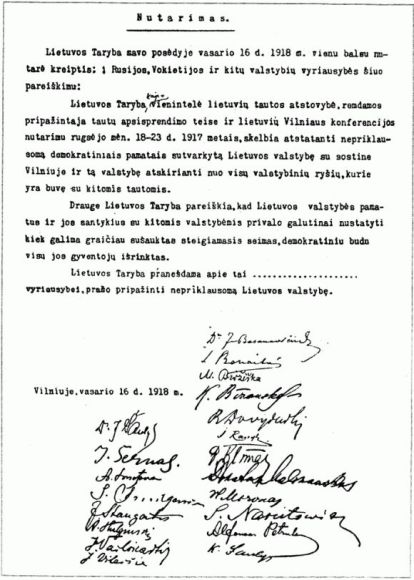

The Independence Act was signed after Dr Basanavičius found a way to reconcile right-wing and social-democratic politicians. The final wording – acceptable to all – proclaimed the restoration of the Lithuanian state, resting on democratic principles and with its capital in Vilnius. The new state was to sever all previous political ties with other nations.

The Act was signed by all the members of the Council, alphabetically. The only exception was made for Dr Basanavičius, who put his signature first.

Forgot where he put it?

The members of the Council of Lithuania signed two copies of the Act: original and duplicate. The original was entrusted to Dr Basanavičius. At the time, the Act was not publicized in any way, its first mentioning in the press didn't occur before 1933. No one knows how the document itself looked, what size it was. It might have been a big sheet of paper with elegant handwriting, yet there are no photographs to document it and testimonies left by signatories themselves are vague in that respect.

It has been put forward that Dr Basanavičius might have forgotten where he put the original copy of the Act, even though his diaries present an image of a very organized man, noting down every detail. Dr Basanavičus' personal archive of books and manuscripts are kept in Lithuanian Literature and Folklore Institute in Vilnius. The archive has been checked for the document numerous times, but the Act has not turned up.

A fresh hope of finding the Independence Act flashed shortly before year 2000. The old librarian Pranas Razmukas, who died in 2002, revealed that, upon Soviet invasion in 1940, he had hidden a pile of documents in the attic of Petras Vileišis palace. A new search was organized, turning up many valuable documents, except the one that everyone most hoped for.

In addition to that, a thorough search has been carried out in the library of Lithuanian Scientific Society. Looking through 28,000 books brought no result, however.

Empty wall cavities

Hope to find the Independence Act was crushed once again in 2006, after searching Lithuanian Literature and Folklore Institute building in Antakalnis. Scientists, equipped with state-of-the-art technologies, thoroughly scanned the building walls for hidden treasures. All cavities turned out to be empty.

The former Petras Vileišis palace, now housing the Institute, was searched hoping that Jonas Vileišis, one of the signatories and brother to the master of the house, might have hid the document there. Jonas Vileišis is considered to be the principle author of the text in the document. The palace had been search before and, with documents and jewels being turning up, so it was hoped that one more discovery might be possible.

Eaten by the bees

The third version of the whereabouts of the Independence Act sounds least convincing. Some researchers have guessed that someone might have hidden the document's original in a beehive, where it got ripped to peaces by the bees. Such theory has been put forward by the US Lithuanian daily “Draugas,” based on memoirs of a military officer to whom the secret was confided by a priest friend, who, in turn, had heard it from reverend Vladas Mironas, another signatory.

According to the story, Mironas was given the original that he later passed to reverend Vladas Jazukevičius, rector of St. Nicolas church in Vilnius. The latter was a beekeeper and hid the document in a beehive.

Duplicate vanished into thin air

Some believe that the original to the Independence Act lies hidden in one of the archives in Moscow. Others claim it has long since been burned or stolen.

The fate of the duplicate is no less vague. It is known that it had been kept in the secretariat of the Council of Lithuania until 25 November 1918, when it was taken, together with the Council meetings minutes, by Petras Klimas who intended to have it published. The Act stayed with Klimas until 18 February 1925 when it was passed to President's Chancery archive in Kaunas. It remained in the archive until the fateful date of 15 June 1940, when the Red Army invaded Lithuania. What happened to the duplicate of the Independence Act after that is not known.

In 2000, a search was carried out in Balsupiai village, Marijampolė district, in the house of book-smuggler Vincas Bielskus. It was presumed that Pijus Bielskus, President Smetona's chief of staff, took the document to his native village and hid it in his brother's house. The entire Bielskus family was deported to Siberia. When they came back from exile, the house was found burnt to ashes.

One more theory has been put forward by Benjaminas Mašalaitis from Marijampolė. He once claimed that the document had been sealed in a bottle and buried in the cemetery of Gudeliai town, Marijampolė district. In 1993 the theory was put to a test – it turned out to be inaccurate.

According to historian Raimundas Klimavičius, there's also a version of the story that, back in 1918, the original document was taken to Lithuania's embassy in Berlin, where it disappeared after 1940.

In 1928 and 1933 two facsimiles were produced to the duplicate of the 16 February Act. The first facsimile reproduces the document exactly as it looked in 1928. In the second one, some flaws of the original were corrected: the background was cleared of soiling, lettering and signatures made sharper, some spelling and typing mistakes corrected.

|

| Facsimile/Independence Act |