“My name is Mary, Renate says, and a woman takes a hallowed egg from the girl's hands. Mary falls into a deep black well, but there's no fear.” This is one of the last phrases in the novel. But before it comes, the reader follows a long journey of poverty, fear, hopelessness. A journey into Lithuania, where poverty-stricken German mothers from East Prussia would send their children after World War Two. They would work in farms there, beg, and whenever they'd get hold of an extra piece of bread, they'd try to bring it across the river Nemunas, to feed their starving families. Šlepikas says his book is about love and sympathy. And memory.

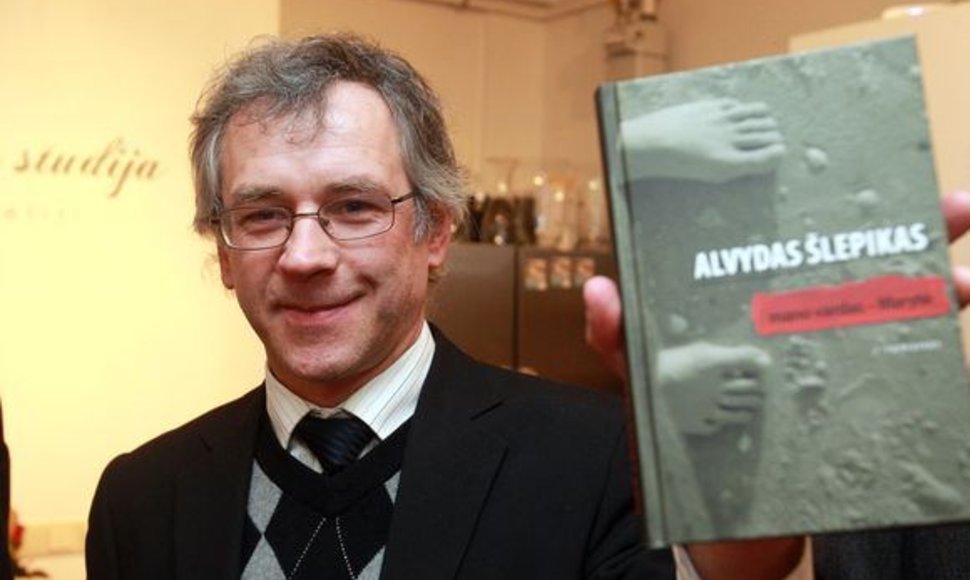

“My Name Is Mary” has been named the book of the year and also awarded Justinas Marcinkevičius Prize and the Writers Union Prize.

– Your novel has been showered with prizes and is now the book of the year. Is it important for you?

– I'll tell you frankly – it is. It was important to be recognized by fellow authors, who gave me the Writers Union Prize. They know what writing is, so their tribute was particularly important for me.

I have never seen myself as someone who writes for the drawer. A writer must want that his books are read and discussed. So the Book of the Year award is also important – it comes from the readers and shows that people still read books and take interest in them.

– I must admit that before reading your book, I'd never heard of “wolf children.”

– There's not much information about the phenomenon. In the Soviet times, it wasn't acceptable to talk about begging German children – such a thing was incompatible with the image of the Red Army as the saviour. In Germany, too, the topic is rather suppressed.

– Why is it so?

– The Second World War is a painful chapter in their history. Germans speak a lot about their own guilt – for starting the war, the Holocaust, other atrocities. Perhaps they feel uneasy pointing out that there were victims in their own midst, too.

– Some of such victims were children who used to cross the river Nemunas from East Prussia – Kaliningrad now – to Lithuania during the war. What drew you to these children and their stories?

– I learned about “wolf children” from late Jonas Marcinkevičius, film director with whom we used to work on scripts. Jonas told me what he knew. We submitted an application to the Ministry of Culture for a film, but they didn't give us any money.

Some ten years have passed since. A producer friend of mine, Rolandas Skaisgirys, introduced me to businessman Ričardas Savickas, whose mother was one of the “wolf children.” I spoke to her a lot, recorded her stories, memories. Ričardas wanted that the subject wasn't lost to oblivion, that people knew about it. We thought of making a film. When we started talking about our plans publicly, we received many calls. People wanted to share what they knew and what they experienced. And so I got into contact with another woman who was also a “wolf child.”

Speaking to her, I had a sense of the time, I felt the air, the sensibilities of back then. Trivial details, hints, silences, historical materials that I've read – all started coming together in a film script I worked on with my poet friend, diplomat Evaldas Ignatavičius. Evaldas was Lithuania's ambassador in Germany at the time. He sent me documentaries about “wolf children.” I watched them and continued studying the subject. Film production got stuck for want of funds. But I did not want to just abandon everything, so I decided to write a book.

– There is a moment in your book where a mother trades her child for a bag of potatoes. Is this detail fact or fiction?

– It is a fact mentioned in a number of testimonies. After the war, Germany encouraged women to have more kids. Families were very big. Imagine a situation where a mother is left alone with six or eight children. They are doomed to die of hunger. So mothers had to choose – let their children die before their eyes, or send them to Lithuania, hoping that they will stay alive, even if never to be seen again. Perhaps they can get a job in a farm, perhaps someone will feed them.

– Judging by the book, it seems that most Lithuanian families, at whose doors these children knocked, would not turn them away. They tried to help them, at least give something to eat.

– “Wolf children” give very diverse memories of Lithuanian families. Some accuse Lithuanians of being cold-hearted, cruel, callous. There are testimonies about families who accepted the strange child, but made him sleep in a barn, with pigs. Others tell about such children being chased away, Lithuanians not even inviting them to get warm. Not to mention giving them work or food.

In my book, I tell about several families that did not turn away from a freezing and starving kid. Most of these children would go through several families. They'd work at one farm for a while, see how slavish it was, and then go somewhere else. They'd live in forests, too, steal for survival. Kids are kids. They had to survive somehow. Elder ones might even try and bring something to their starving siblings.

– But in general, your book is quite uplifting. There is little cruelty that one might expect right after the war.

– I did not want to ponder on cruelties. I aimed for a clear narrative that would have moments of hopelessness and of hope. A story that would not leave readers indifferent. I would wish very much that teenagers read the book. Perhaps it would help them realize what hatred means, war, how long human suffering can last, how it follows not just the afflicted person, but generations after him.

– Or try and imagine feelings of a mother who covered her daughter's face with manure so that soldiers wouldn't touch her.

– Yes, it is true.

– You've also published two poetry books and a collection of short stories. You also write film scripts. Critics say that the author of the novel is Šlepikas-the-poet and Šlepikas-the-scriptwriter. What do you make of such titles?

– Contemporary literature is extremely diverse and employs a wide range of techniques. I needed the novel form – which perhaps resembles a script in some sense – in order to move the story forward. So that the story, packed with facts and details, isn't too long and boring. My ambition wasn't to write a historical or a psychological novel.

My goal was simple – to tell a story and make the reader feel the air of the period, turns and twists of human fate, coldness, warmth, fear and hope. I do not know if I succeeded. I'd be happy, though, if the book left room for readers' own thoughts and reflections.