Death caused by the regime

The day is 14 May 1972. Midday in Kaunas City Garden next to the Musical Theatre in the town's central street. A dark-haired youth of rather marked features takes out a three-litre jar, pours gasoline it contains onto himself, exclaims “Freedom for Lithuania!” and lights a fire. Flames quickly embrace his entire body. People take off their clothes and try to put out the flaming young man, but he burns and passes out. Emergency medics arrive and take him to hospital. 14 hours later, 4 AM on 15 May, Kalanta dies – heavy burns of entire body. His relatives come across an inscription in his diary: “My death is only to be blamed on the regime.” And a signature underneath.

|

| nuotr. iš asmeninio archyvo/Romas Kalanta |

“Do not blame anyone for my death. I knew I would have to do it sooner or later. I hate the socialist regime. I am not good for anything. Why should I go on living? So that this regime kills me off? I'd rather do it myself... there won't ever be freedom here. Even the word 'Freedom' was banned,” the youth wrote in the last pages of his diary.

Crowds in the streets

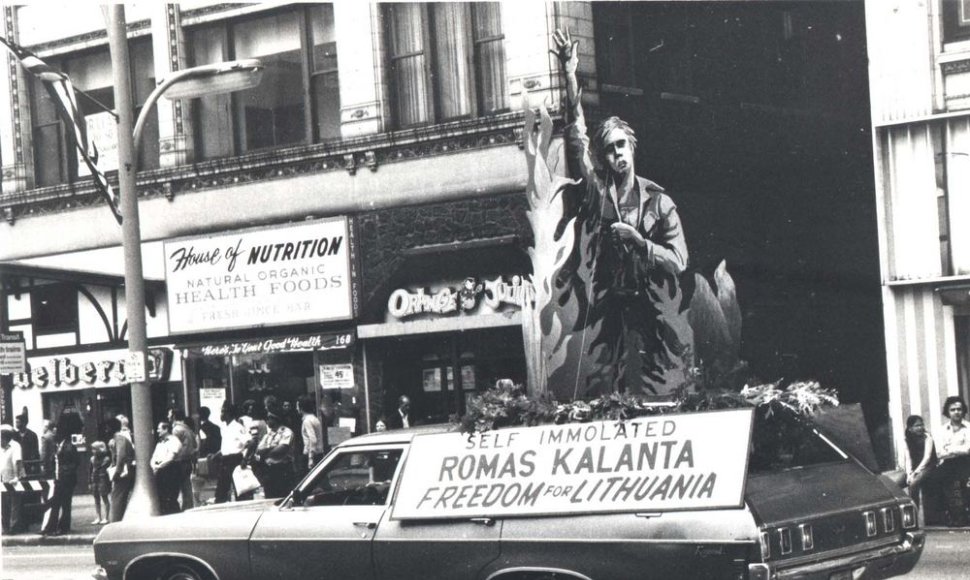

It was the first incident of this kind in the Soviet Union. On 18 May, the KGB, completely at a loss, moved forward Kalanta's funeral two hours, so that most people couldn't catch it in time. The people, who marched towards Kalanta's house to pay their respect and discovered they were late, were furious. On the 18-19 May, over 3,000 protesters hit the streets – not only from Kaunas, but people from neighbouring towns and villages. Security officers and the police chased them, detained, and charged with hooliganism.

|

| Eriko Ovčarenko/15min.lt nuotr./„Šiurkščios viešosios tvarkos pažeidėjų grupė 1972 m. gegužės 18 d.". |

On the day that Kalanta was laid to rest, two school teachers from Molėtai – one teaching Lithuanian and the other History – were taking their pupils on a tour to Kaunas. A crowd was flocking to Laisvės Avenue, Kaunas central street. The teachers had not been aware the place would be a rally site and therefore were surprised to see so many flames and piles of red tulips – it was their high season. The teachers watched young people grouping in eights and peacefully chanting “Lithuania.” In order not to be harassed by the authorities, they behaved very orderly and made little noise. That was how the two women discovered what had happened, since there was no mention of Kalanta's deed in the media. The teachers returned home shocked and spread the word among their relatives and acquaintances. Everyone did.

Kalanta's act gave hope to people that independence was possible and contributed to subsequent struggle. The 14 May was later named the Day of Civil Resistance.

Declared insane

One week after Kalanta's self-immolation, similarly-worded announcements appeared in two dailies, the Kauno diena, on 20 May, and the Komjaunimo tiesa, on 21 May. The Komjaunimo diena wrote: “In connection to received inquiries regarding Kalanta's suicide on 14 May in Kaunas Musical Theatre garden, the city prosecutor's office announces that an investigation is in progress. Inquest bodies ordered examinations, including forensic psychiatric examination by forensic medical psychiatry experts team who also studied available documents: Kalanta's notes, letters, drawings, school essays, as well as testimonies by his parents, teachers, friends; they came to a conclusion that Kalanta was a mentally ill man and committed suicide under such condition.” The news soon spread abroad.

A team of five psychiatrists, summoned in 1972, concluded that Kalanta was schizophrenic. As proof, they quoted the fact that the youth took his life in such a quaint manner; the fact that he wore long hair; one school essay where he claimed that Lithuania would be free one day – back in the 1970s, such claims sounded like lunacy.

The view that Kalanta was not of sound mind persisted in some quarters – as late as 2008, author and healer Filomena Taunytė wrote a book “How Much A Soul Weighs” where she made an unequivocal assumption that Kalanta was mentally insane. However, in 1989, another commission of four psychiatrists declared – for lack of any evidence to the contrary – that Kalanta was sane and had sensitive soul.

|

| LYA nuotr./After Kalanta's self-iion, spontanious demonstrations errupted in Kaunas. |

Deliberated suicide

Director of Vilnius University Psychiatry Clinic Dainius Pūras, who was one of the four in 1989, recalls that the commission spent several months trying to reconstruct the last year of Kalanta's life: what he felt, whom he talked to. “The commission met with many of his friends, acquaintances, and people told everything as it was, for the first time. Just imagine how these people had been interrogated in 1972!” Pūras recalls circumstances of the inquiry.

“The deeper the commission went into Kalanta's personality and all the circumstances, the more clearly and unanimously they came to a conclusion that there was no evidence whatsoever that Kalanta might have been mentally disturbed or suffered from a mental disease.

“We were very careful about re-examining this case where our colleagues had diagnosed, also posthumously, a serious mental disease 17 years before. Not only did we consider schizophrenia – and that diagnoses must be based on solid symptoms – but also depression. People told us that Kalanta was a guy just like any other. He wasn't a saint, nor was he an ill man. His friend recounted how they used to drink together, meet with girls, play football, and discuss politics.”

The commission, Pūras says, did not interview people who had actually witnessed the young man's self-immolation. He notes, however, that Kalanta's essays and diaries contained many details suggesting he had been consistently planning his self-sacrifice, even though wavered somewhat.

“There were entries like “Why can I not do it.” The man wanted to live, but at the same time thought of contributing to efforts of fighting the regime. He was suffocating, he could smell the spirit of captivity. In my opinion, it was not just to do with national oppression, but a much wider one – people were denied their rights,” the psychiatrist says.

Screaming in pain

Romualdas Balčys, 58, who now lives in Vilnius, says he was an actual eye-witness to Kalanta's deed. “It was Sunday. The Musical Theatre was showing “The Girl Looking for A Fairytale.” I though: Why not go and see it, since I had to report for military duty on 22 May. My friend Saulius Zykus and I came but we didn't get the tickets. It was five minutes to twelve and we didn't get into the play.

“So there we are, sitting on a bench. Smoking and conversing. A Russian officer sits next to me, with a woman with a baby. We have been sitting there for an hour when I see Kalanta crossing the lawn, very sad and preoccupied, wearing a jeans jacket. He carries a three-litre jar. But how could I know it contained gasoline! I thought it was water. Zykus had a thing against long-haired guys, he says: Ah, pay no attention.

“Kalanta sits on the ground, leaning against a tree trunk, then he stands up, comes forward, grabs the jar, takes the jacket off, opens the lid and pours gasoline onto himself. Saulius tells me: Do not look at him, he is working the audience. We turn away and suddenly – explosion!

“I turn my head and cannot understand what is going on. Kalanta, bent, screaming in pain and rolling on the ground towards a bathroom in the square corner and the grass is all aflame where he has passed.

“A gypsy woman ran to him first and tried to put him out with her skirts. Then the officer threw a jacket on him, we ran towards him too. And Saulius, who was very pragmatic, told me: Romas, let's go, the cops will come soon, we'll have to be witnesses.

“No one thought it would develop into such a big thing. We didn't realize it had to do with politics. My mum later told me that while I was in the army, the KGB came to the house asking for me. They knew I had seen it.”

Balčys says he does not want to destroy a legend, but Kalanta did not exclaim “Freedom to Lithuania!” before setting himself on fire, as everyone says. At least Balčys, who was 10 or 15 metres away, did not hear it. He says that not many other people saw the self-immolation - besides himself, his friend, the officer, and a few gypsy women.

Freedom idol

Romas Kalanta was born on 22 February 1953 in Alytus. He was 19 when he died on 14 May 1972 in Kaunas.

He was a night-school student and had spent some time working in a factory.

Kalanta played the guitar, wrote poetry, was a well-read, peaceful man, a little shy. He sympathized with hippies and wore long hair. He was, however, member of the Communist Youth organization, like majority of his peers.

In 1990, his grave was declared a local historical monument. In 2000, he was posthumously awarded with the First Order Vytis Cross Medal.

In 2002, a monument was unveiled in Kaunas, on the site of Romas Kalanta's act. The pavement was inscribed with his name and the year – 1972.