Peasants would only travel within the lands of their seigneur, occasionally visiting relatives owned by neighbouring landlords. Petty nobility would make trips to local sejms (in powiat centres).

Higher noblemen would go to national Sejms and tour the entire country for reasons of managing their estates, finances, politics. Many even ventured abroad with diplomatic assignments or for pleasure. Well-off noblemen would send their sons to Western Europe to study or to “see the world.” Clergymen would go on pilgrimages, visit Rome and the Pope. Few journals of such travels survive to this day, though, as many noblemen did not go to foreign lands even once in their lifetime.

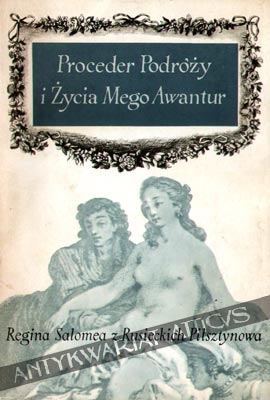

There are exceptions. Researchers of travelling in the Grand Duchy point to one special case – the travel journal of one noble woman from the early 18th century, Regina Salomea z Rusieckich Pilsztyn (Regina Salomėja Ruseckaitė-Pilštyniova). The author travelled as far as Istanbul, spent some time living there, and afterwards visited great many places in the Grand Duchy, Poland, the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires. Her impressions, written in a highly readable style, were a joyful discovery to researchers of the Grand Duchy history.

Unhealthy art of healing

Very little is known about the woman, so historians must rely on her own accounts of her life. She wrote that she was born in 1718, in Novgorodok Powiet. From an early age, Regina Salomea took interest in shooting and would always carry a set of pistols or a riffle with her. At 14, she was married off to a bright Lutheran oculist and doctor, Jacob Halpir, who left for Istanbul soon afterwards, taking his young wife along.

|

| Regina Salomea's travel journals were pulbished in Poland in 1957 |

Living in the Ottoman Empire, Regina Salomea acquired some mastery in the medical arts from her husband as well as Turkish, Italian, Maltese doctors. Even though she successfully treated patients, she also believed in sorcery. She noted in her diaries that she had been taken ill by witchcraft on numerous occasions. Regina Salomea believed that one of her legs withered and was half-cubit shorter because someone had given her an evil eye. Later in her life, she lost command of both legs and arms as well as her mental faculties – she often felt like a child and used to see a long-bearded monster lurking outside her window.

When her husband's profession took him to Sofia, the noble woman took up medical practice, too, and treated female patients. In the town of Philippoupolis (now Plovdiv in Bulgaria), Regina Salomea treated the daughter of a local nazir (governor) with worms. The kid took medicine made of aloe, saffron, myrrh, sulphuric acid, and wine spirits. Unfortunately, the girl died. Then the doctor herself took the medicine. She survived and only that saved her from execution.

In the custody of the king of thieves

Regina Salomea also describes what was one of the biggest adventures in her life when she was crossing the Balkans. It was difficult to travel across the mountains in a carriage, so she rode on a horseback dressed in men's clothes.

On her way, she joined a caravan but was soon taken prisoner by a local thief, Sary Husein (the Brown Husein). He recognized her for what she was. Regina Salomea cured the thief king and his son's father-in-law of eye diseases. The woman was royally rewarded and safely returned to her husband, who died not long after. Regina Salomea was left with a daughter.

Husband bought from the sultan

Upon learning about the defeat of the Austrian army at the hands of the Ottomans, she ransomed four Austrian prisoners of war from the sultan's captivity. Relatives of three of the soldiers paid her back the ransom, but not the fourth one. Joseph Fortunatus Pilstein was an officer of the Austrian army and came from Krajina (present-day Slovenia). He became Regina Salomea's second husband.

The two returned to Novgorodok. Field hetman Michal Kazimierz "Rybenko" Radziwill accepted him to his army, while Regina Salomea continued to practice medicine. Later, she decided to go to Russia and free several Turks from captivity.

She travelled to Saint Petersburg via Vilnius, Biržai, Riga, and Narva. A few successful operations there brought her fame and she was introduced to Empress Anna Ivanonva. The Empress treated the guest kindly and agreed to free Turkish prisoners kept in Reval (Tallinn) and Narva.

Regina Salomea returned home through Biržai, Ukmergė, and Vilnius, settling in Polesia. Her husband was sent to Zhovkva (now Ukraine), near Lviv. Despite being pregnant, she travelled via Wroclaw, Olomouc, Vienna, and Ljubljana all the way to her husband's home.

Later Pilsztyn settled in Vienna and lived on the doctor's trade. While in Austria, she gave birth to a son. Her second marriage, however, was not a happy one. The husband, Regina Salomea wrote, was susceptible to splashing money and drinking. When she left for Turkey, the husband kidnapped her daughter and even attempted to poison Regina Salomea. After unsuccessful attempts to reconcile, Pilsztyn divorced her husband and remained alone with her children.

Passion for a younger man

After the unsuccessful marriage, Regina Salomea had an affair with a man seven years her junior, someone to whom she referred to in her memoirs as “amorato.”

She wrote in her diaries about how she would let him exploit her, while he took her money. On one occasion, Pilsztyn left her kids in his custody and departed; upon her return, she discovered that her son had starved to death – but not even after this did she break up with her lover. She went to Kiyv and he followed her. The woman even went to a court of the Russian Empire and secured a warrant for the former partner's arrest. However, the two met accidentally in a monastery and reconciled.

In sultan's harem

Pilsztyn spend considerable time living in the Ottoman Empire, in Hotim (now Romania). She was accused of providing help to people who fled the Empire to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. To escape prosecution, Regina Salomea left for Istanbul for the second time and became a doctor to the sultan's harem.

Pilsztyn's diaries describe in great detail everyday life of the time. She was most impressed with royal palaces she had visited. Awe-struck by the beauty in the palace of the liberal sultan Mustafa II, she thought it was heaven on earth.

She also loved Saint Petersburg. The doctor commended that there were no shanty houses lurking in the shadows of palaces here, unlike the ones she saw in Vienna or Istanbul. Pilsztyn was positively mesmerized by Empress Anna Ivanovna's court and she wrote down many anecdotes she heard about Peter I and other Russian noblemen.

Catalogue of nations and customs

The woman's narrative is a gripping and important testimony to 18-century life. Hers was a rather extraordinary career – very few women of the time succeeded as doctors. Pilsztyn, meanwhile, had no trouble finding patients and made a decent living on her trade.

The author sharply observed people of foreign creeds and nationalities. She sympathetically described customs of the Ottoman people. The Turkish script was very complicated, she wrote. Turks themselves, meanwhile, spent their days reclining in coffee houses and listening to music. True, she felt anxious over the cruelty of the sultan and his officials against Bulgarian and Serb insurgents, over repressions against Christians. She preferred Russians to Austrians for their Slavonic hospitality.