Over the last half-century, the global population has grown from 3 billion to 7.1 billion. The growth curve should become less steep in the coming decades, but it is estimated that, by 2060, the planet will have to support a human population of almost 10 billion.

In Europe, the continent that is now home to about one tenth of the global population, the increase will be less sharp. By 2045, low fertility, emigration, and ageing might reverse the trend entirely.

Depopulation in Europe will make fighting economic crises increasingly difficult. Bad as it may sound, Lithuania is already experiencing the effects that only await the rest of the continent in the future.

In 2011, sixteen out of 27 EU member states reported net migration gain. The rest, including Lithuania, lost more people to emigration than gained through immigrantion. Therefore countries like Lithuania will be more hard-pressed by the effects of ageing population and low fertility than others.

Settling elsewhere

Mass emigration from Lithuania started when the country joined the European Union in 2004. Initially the silver lining blinded everyone to the ominous storm clouds – Lithuanian emigrants would send money they earned abroad to relatives in Lithuania, thus fuelling economic growth back home. In the beginning, expatriate support was almost double what the European Union was giving.

Even in recent years, there have been talks about record-high sums of money transferred by migrant Lithuanians to their families at home. The sum total of these transfers, however, is only one third bigger than it was in 2006 (LTL 4 billion n 2011, compared to LTL 2.9 billion in 2006). Bearing in mind inflation and a significantly larger Lithuanian emigrant community, that means that expatriates are actually sending home less money than before.

And that, in turn, means that they are settling in abroad rather than just leaving for limited periods of time.

|

| Gitanas Nausėda, expert on pretty much everything |

“Lithuanian communities are forming, some migrants settle in, they invite their families and friends to join them, perhaps in order to feel more at home, to surround themselves with people they love in their new homes. Migrants are settling in to the extent that it might be impossible to get them come back in the future,” says economist Gitanas Nausėda, adviser to the president of SEB Bank.

As the first wave of migrants left Lithuania, it was hoped that, having saved up enough money or earned their university degrees, most would come back and serve their country. Such hopes are failing, however.

“What we witness today is a veritable loss of emigrants, while before, we had hoped they'd come back. Even the fact that it was mostly young people who were leaving didn't seem so alarming, because we could still have expected them to return after finishing their studies. But if they are not returning, that means that what we've invested into educating these people was a charity to other, more affluent, countries,” says Jekaterina Rojaka, chief economist at DNB Bank.

Viscious circle

Economic growth requires growing productivity and labour force. If the latter becomes more scarce, it might be offset by increases in labour productivity and export.

At the moment, income of an average Lithuanian is several times smaller than that in most EU countries.

“If we could achieve that this gap be measured in percent and not in times, I think that at least some migrants would choose to live here. Unfortunately, it is not the case,” Nausėda says. He notes that economic motives are among the most important incentives to emigrate. Even though many Lithuanians are forced to do lower-status jobs abroad than they used to at home, but they are more happy with the standard of living that their jobs afford them.

According to Nausėda, Lithuania could become a more attractive country to live and work in within five to ten years: “In theory, economic growth is possible under such circumstances. Growth could be achieved by working in foreign markets and successful exports. This is our only option, because administrative and promotional means probably won't do much [to get migrants to return].”

Faster economic growth would mean higher wages. If salaries become at least comparable to those in Western Europe, emigration should halt and, in turn, give even more boost to economic growth.

“If salaries in Lithuania grow five to seven percent a year, that is hardly perceptible. But it's like the straw on the camel's back. One straw after another – and the camel's back breaks. We need to be patient,” Nausėda believes.

In order to keep labour force from emigrating, it is important to create good employment opportunities for youth. At the moment, young people with little work experience are particularly hard-pressed when it comes to employment and therefore often opt to emigrate.

Lately, however, youth unemployment has been dropping faster than overall unemployment. The statistic might indicate changing attitudes among employers or that unemployment reduction programmes are starting to bear fruit.

No borrowing

Lithuania's sovereign debt currently stands at about LTL 50 billion. Meanwhile the country's population is under three million and continues to fall. Therefore paying back the debt will be increasingly hard in the future.

“When demographic trends are negative, state debt per capita automatically grows. Inflation could be a solution – everyone knows that one litas today is worth more than in a year. The general trends are not pleasant and we must carefully oversee any increase in our debt. Borrowing might be fatal, if we do not have a clear strategy for how we're going to pay it back in the future. Nor can we afford to take on huge projects without having a clear idea about future dividends and a plan on how to cover the expense,” Jekaterina Rojaka says.

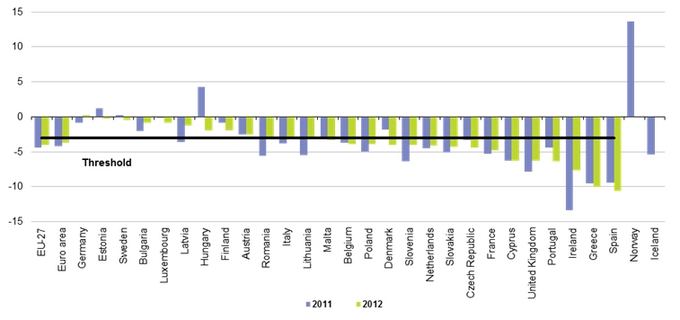

Last year, only one EU member state reported a budget surplus, Germany. All other governments had to borrow.

|

| Budget deficit in EU countires |

Lithuania's budget deficit and sovereign debt is rather small compared to most countries on the continent, but public spending still exceeds budget revenues.

“All we can do is cut our fiscal deficit to a bare minimum to keep public debt from growing even further. I think that policymakers are moving in that direction. Everything is happening much slower that we'd like to. A balanced budget will not be achieved in a year, but at least we have a deficit that does not make our debt skyrocket,” Nausėda comments.

Expatriate Lithuanians, though, care less about public debt than about average wages. And on a more optimistic note, statistics also indicate that happiness index does not correlate with national wealth – i.e., the happiest countries on planet are not the richest ones.