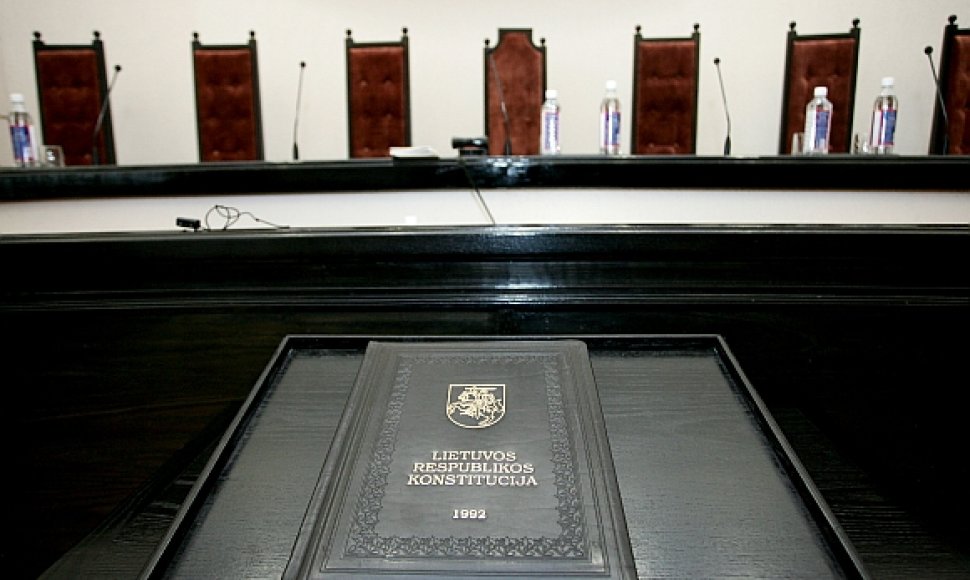

Twenty years ago, on 25 October 1992, people voted overwhelmingly in favour of the proposed Constitution for newly independent Lithuania. The law, drafted amidst fierce political and legal debates of the Supreme Council-Reconstitutive Seimas, was put to a referendum vote and endorsed by 75 percent of the voters – or almost 57 percent of the entire electorate.

|

| BFL/Tomo Lukšio nuotr./Juozas Žilys |

The working group which assisted politicians in preparing the Constitution was led by Dr. Juozas Žilys, who later became the dean of the Faculty of Law at Mykolas Romeris University. The lawyer believes that the document played an unequivocally positive role in the development of Lithuania's political and legal system, despite the recent debate in the public about its drawbacks and a need to change.

“On the other hand, social changes automatically inspire debate. Everyone is free to speculate what could be done differently,” he says. “However, the debate must start from some clearly observable problems and follow constructive arguments.”

Asked if all articles in the Constitution are still relevant to life in Lithuania, he admits that one might consider amending certain provisions – like the number of MPs in the Lithuanian Seimas. In 1989, when the population of the country was 3.8 million, it was decided on 141 representatives in the Supreme Council. As the population has dwindled to just under 3 million, some political parties propose cutting down the number to 101 or even 71.

“Right after the elections, we must put together a group of politicians, lawyers, sociologist to assess what has happened in our society and present reasonable suggestions for the electoral system. Reducing the number of deputies in a representational democracy is not a bad thing per se, especially since it would mean saving taxpayer money. In general, though, it is good when more people represent voters.”

Žilys stresses that the question should be taken up by the new Seimas as soon as possible, as the new election cycle will inevitably bring unbalanced debate, “constitutional attacks,” and superficial populism.

Many articles need to be changed?

Žilys says double citizenship, which has perturbed politicians and Lithuanian expatriates alike for several years now, is a political issue rather than a legal one: “It has to be further discussed, bearing in mind our current situation and the scope of emigration.”

Meanwhile Aurimas Tarantas, one of the drafters of the Constitution and currently Lithuania's ambassador to the Czech Republic, disagrees. According to him, when authors of the document wrote that double citizenship was possible in explicitly stated instances, they meant that people were to be entitled to it in exceptional cases and not as a matter of course – an interpretation that was upheld by a ruling of the Constitutional Court. It said that resolving the issue required passing constitutional amendments.

Taurantas, who is also a signatory of the 11 March Independence Act, is sceptical about motions to reduce the number of MPs: “Even if we could save money this way, it would not be enough to feed the poor. What matters is the quality of their work, not their numbers. Fewer MPs might be more susceptible to outside influences.”

|

| Organizatorių nuotr./Vytenis Andriukaitis |

MP Vytenis Andriukaitis, who also contributed to drafting the Constitution, maintains that both questions are of secondary importance and reeks of populism. According to him, the pressure over double citizenship mostly comes from US Lithuanians, not the ones in the EU. As foreign and border protection policies have been delegated to Brussels, citizenship, he says, remains among the key criteria of an independent state.

The social democratic MP maintains that the problem of contracting population is not a constitutional issue, since Lithuanian citizens have a civil obligation to vote irrespective of where they reside – therefore all talks about reducing the number of MPs are just hot air. There are much more pressing issues – like harmonizing EU Fiscal Compact treaty to Lithuania's fiscal policy regulations; implementing a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights regarding the current ban on impeached officials running for public office.

“At least two issues are hot potatoes now,” Andriukaitis tells 15min. He adds that other questions to consider are the office of Vice-Prime Minister and municipal self-government reforms: one-tear municipal government and a small number of elected officials therein hint at a certain lack of democracy.

At least ten versions

After Lithuania declared independence from the Soviet Union, the state was run according to the Provisional Basic Law which was based on the Soviet Constitution amended in 1989. Different political forces had diverging visions for the future state and made changes to the document almost each month. The young state was in desperate need of a stable constitutional law.

In order to draft a constitution, the Supreme Council formed a commission comprised of delegates from all parliamentary parties and chaired by Kęstutis Lapinskas. A working group of the most outstanding legal professionals in the country – led by Žylis – helped draft certain sections of the law.

Work progressed more or less smoothly until April 1992, when differences began to emerge regarding state structure and relationship of the parliament, the president, and the government. Commission members Zita Šilčytė, Liudvikas Narcizas Rasimavičius, and Egidijus Jarašiūnas presented an alternative project inspired by Lithuania's 1938 Constitution which envisaged a president elected for 7 years and unaccountable to any other institution.

More projects were submitted for discussion. Various political factions came up with at least ten of them. Some of them gravitated towards the more progressive example of Lithuania's 1922 Constitution, while others seemed modelled after the 1938 Law, adopted during the dictatorial leadership of President Antanas Smetona. It was the latter that was formally reinstated upon declaration of independence in order to underscore the continuity of the inter-war Republic of Lithuania. True, it was suspended right afterwards and a new Provisional Basic Law was passed by unanimous vote. The new constitution was to be written anew and not following old examples.

Controversial issue of the presidential office

After a referendum was called in May 1992 on reinstating the president's office (merely 40 percent voted in favour), parliament was facing a constitutional crisis. Right-wing delegates would assemble in one room while everyone else in another. The two sides could not agree, even though the Supreme Council had ordered Lapinskas and Jarašiūnas to combine their respective projects. It was not until August that both camps managed to reconcile their differences and sit at one table to discuss the constitution.

Speaker of the Supreme Council Vytautas Landsbergis himself chaired a group of deputies charged with reaching an agreement. A political breakthrough occurred in July, after which lawyers could start working to give it a more legal shape. “The final agreement was not reached until the very last minute – in the beginning of October, in early morning, 2:30 AM or so. I remember, it was very cold, we were all wearing wool sweaters,” Taurantas reminisces.

“It was a collective effort by lawyers and representatives of all parliamentary parties. We would work in Landsbergis' office until dawn,” Žilys recalls. “Prepared wordings would be taken to parties, discussed in Supreme Council plenary sessions, endorsed or rejected. Lapinskas, Romualdas Ozolas, Andriukaitis, Eduardas Vilkas, Landsbergis, Egidijus Jarašiūnas were active participants. There was no single person who dominated the process. Sure, the project underwent many changes and the final wording was a compromise. Vilkas at one point commented thus: We can now speak of a Constitution.”

Authors had to work fast, pressed by the approaching deadline of general elections and constitutional referendum. “These were hot days for politicians who had to decide the fate of Lithuania. Will we be left without a constitution, will the Supreme Council be dismissed without presenting the document? The Provisional Basic Law was a remnant from the past. A democratic regime had to be based on a modern constitution,” Žilys says.

According to him, the hottest debate centred around powers to be given to the president: some politicians wanted a stronger office, while the commission leaned towards parliamentarism. Most delegates in the commission maintained that the president should not be able to dismiss parliament under any circumstances. One proposal envisaged that the president could not have any bearing on forming the Government, while, according to another, he or she could dismiss the Cabinet at will. There was one proposal to have parliament elected every six years, changing one third of its members every two years.

Neither side had a clear advantage, so it was difficult to come up with a document that would be endorsed by a Supreme Council majority. “One could not adopt the Constitution without acknowledging the other side. We were not working on a Government or party project – we were building a politico-legal programme for the entire nation. Therefore we needed to seek out common ground,” the lawyer stresses.

Taurantas, who was one of the few who did not clearly align with either group and mediated between them, gives a similar account: “The Constitution was built on a hard-won agreement, after finding a common denominator which was acceptable to all sides and still bands the Lithuanian society. We had to take opposing parties – who were not speaking to one another – by their ties, drag them to one room, and make them talk. In actual fact, common sense prevailed as well as understanding that if the Supreme Council disbanded without leaving a constitution, a chaos would ensue. Unfortunately, today people keep forgetting that in order for things to work, an agreement must be sought daily.”