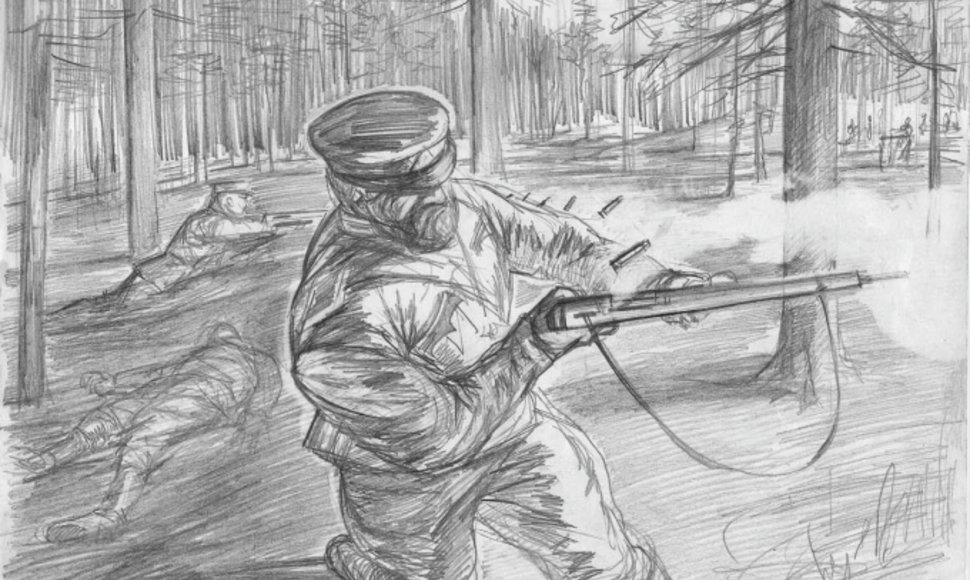

Back in 2003, Lukošaitis, 32, created a series of drawings entitled “Resistance,” dedicated to the memory of Lithuanian post-World War Two guerilla resistance. The series comprise of 100 drawings in pencil and did not receive much attention in Lithuania, having been exhibited only on several occasions.

However, Lukošaitis' drawings caught the eye of foreign curators – in 2004, he took part in international contemporary art biennial in Saõ Paulo, while Phaidon published some of the pieces in its book “Vitamin D.” A year later, the entire series was bought by Denmark's Louisiana Museum of Modern Art.

|

| Mindaugas Lukošaitis, Resistance |

The hundred drawings of “Resistance” were exhibited next to Pablo Picasso's works.

In an interview to 15min, Lukošaitis talks about the power of imagination that allows a sharper look at history, the relevance of post-war resistance, search for an identity, and the spirit of patriotism – in history as well as everyday life.

- As the saying goes, one must first find a proper relation to the past in order to meet the future. Is that why you chose to tackle the resistance? How have your views on the past changed as a result?

- Without history there is no life. Only in Mars, where no one owes anything to anyone... The wind blows dust across the deserted plains, nothing and everything reigns there. A human being, on the other hand, is constantly remoulding his own life, that of his nation and family, and he does so by looking essentially in two directions – the future and the past.

The whole hysteria about emigration blankets two key issues. To my mind, these are alcoholism and family policy.

Attitudes inevitably change after each glance to the past. History is like a toolbox, you take whatever you need at the time. The opening of “Resistance” coincided with the year Lithuania joined the European Union. Everyone was preoccupied with issues that were quite similar to those raised by resistance fighters: What kind of Lithuania we would like to see?

In my family, the issue of nationality has always been very important. We spent much more time debating about life than about a living. However, the idea for the series was inspired by the society's attitudes as we were entering the EU. I can recall the day of the referendum and what I was thinking very vividly. I was telling myself that it was one more opportunity to move further from Russia – and then we could see what would happen next.

- You drew the pieces intuitively, using imagination, and you became seriously interested in the topic only after you had finished the series. Does reality surpass imagination? Does the experience inspire patriotic feelings in you, urges you to stay in Lithuania while hundreds of others flee?

- One often hears emigration being set off against the resistance, as if these were two opposite poles. But there are more questions to be raised: How do we perceive emigration and resistance at certain moments in time? To live in Europe without moving – at the same time wishing for the nation to prosper – is simply impossible.

Someone always has to move someplace, someone must live somewhere only temporarily, permanently, or for good, study and teach others here and elsewhere, bring something and take something away, etc. There has always been and will always be problems, but I know that slogans like “Lithuania for Lithuanians” will certainly not salvage us. Much like we won't salvage Africa by handing out condoms.

|

| Mindaugas Lukošaitis, Resistance |

Sure, it is easy to look at everything simplistically. But the whole hysteria about emigration blankets two key issues. To my mind, these are alcoholism and family policy. Lithuanians hardly form harmonious families any more, they do not bear children or have very few. What to do? I suggest we start with strict, even draconian restrictions on alcohol use. And once the head is sober, we'll be able to start thinking what to do next. Firstly, how to make the nation more populous instead of holding people by their feet so they do not leave.

To answer your question about the drawings and imagination, it is more important to make an issue relevant than to give a faithful documentary visualisation. Some means are more unexpected and inexhausted than others – so they draw more attention. That is what must have happened to my drawings. It could be a challenge to every Lithuanian – to present the topic of the resistance in an interesting way.

- When did you realize that you wouldn't be able to contain yourself within several drawings? That it had to be an entire series? Is there some symbolic underpinning behind the figure 100?

- The number of pieces is an entirely secondary and technical issue. It was more important to make sure that the drawings did not repeat, that they created the impression of multiplicity, at the same time not being tiresome in superfluity or didactic insistence – look, this is all very important stuff!

We could ceaselessly pump the subject of the resistance without it amounting to anything, just overexploitation. What is important is not only reminding of the historical period, but how and to what extent you reveal the essence of the topic by doing so. Does the action itself have a moral vector to it? Is there an evil scheme behind?

- You chose a rather simple form – pencil on white paper – to represent scenes from the life of resistance fighters. The form neither excites nor shocks – red blood is more disturbing than a black spot.

|

| Mindaugas Lukošaitis, Resistance |

- I cannot stand when people go into unreserved adoration and praise without giving it a second thought. Blood, just like gold, is a complicated material and mastering it is a great challenge to every creator. Gold is luxurious and vulgar. Blood is brutal. So it is very difficult to construct a narrative that is not kitschy. You can go over the top very easily. Even though my drawings are done in black pencil, the things they depict are very gripping.

- The series was not met with much attention in Lithuania, but it was much more enthusiastically received by foreign art curators. Is that another instance of the impossibility of being a prophet at home?

- The pieces travelled from one exhibition to another and were finally presented in Denmark. Suddenly, someone wished to purchase them. Bearing in mind that the interest came from a major museum, the price offered was relatively modest. But still, it is a sign of great recognition for me – my drawings will get exhibited more than once, while they might have simply bought them and put them in a warehouse to collect dust... It is an internationally renown museum storing the best art pieces in its collections.

Lithuanians have Lithuania, while Danes and the world have one tiny story in pencil about the history of our country.

- It seems that we were unified a little by the recent Olympic Games. As an artist, how would you paint the portrait of a Lithuanian? What kind of Lithuania do you see while living outside the capital city and the urban buzz?

|

| Mindaugas Lukošaitis, Resistance |

- I see a Lithuanian who is still woozy after anaesthesia. Fifty years of soviet anaesthesia have left a mark. I can see how this Lithuanian is doing his utmost to wake up – he sucks air into his lungs, moves, exercises: He emigrates, builds, borrows, and does all he can, but it seems that he is still not fully in his wits and faculties. He is looking for his values and identity. It's hard to tell how well we manage to cling to life, perhaps it's just an illusion? I do not know, since I am, perhaps, myself still a little woozy. I raise the very same questions: Who am I?

Paradoxically, we keep seeing instances of the younger generation – people who matured in an independent country – regarding Lithuania as a barn in a collective farm, where you can scoop without storing. Parents scooped and children saw them scooping.

But I believe that if tanks came to us, as they did in Georgia, and desecrated what was really dear to us, we would witness an outburst of patriotism that is anything but banal.

Neither caricature, nor pathos

The resistance and the Holocaust are the joyful and the painful secrets of my nation.

In his new series of drawings, “Jews. My History,” Lukošaitis tackles another side of Lithuania and the painful topic of the Holocaust.

“A drawing and historical subjects fit together in a very peculiar way. A drawing in itself makes no claim to being a faithful documentation, so it does not oblige the viewer to interpret the scenes it depicts as “true” or “false.” We instantly recognize it as a subjective depiction. Then all we can do is watch imagination building a history for us,” Lukošaitis says.

It took him a long time to tame the subject.

“It cost a lot of internal resources to keep all the external tensions and the white noise from interfering with my thoughts and reflections. A mind is prone to picking up a cliché, but once you give it a second thought, you realize that it is too shallow and misleading. I saw that I was full of rubbish. It took some time to clean it up,” he admits.

He underwent two developmental periods while working on “Jews. My History.”

“At first, there was only fear. On several occasions, I decided to give the project up for good. Both the political and the historical contexts are too charged, so I need to reflect on my visualizations very carefully – you cannot indulge in either pathos or caricature, while it is so easy to go over the top. You can see how, in your head, you line these people against the wall and shoot, but how to draw it? In the end, I came to terms with my history. With things that I previously pushed out, reluctantly evaded. I had to confront and acknowledge the fact: Yes, it is my history. If it weren't for the series, I would have never come to certain revelations that have changed both my perceptions of my nation's history and worldview in general. The resistance and the Holocaust are the joyful and the painful secrets of my nation,” Lukošaitis summarizes.