Since entering the Euro-Atlantic geopolitical space, Lithuania has been searching for new foreign policy directions. Ambitions to become the centre of an ill-defined region have failed, mainly due to lack of real influence, and so did plans to pursue more pragmatic policies, i.e., improve relations with Russia and Belarus and step up cooperation with EU majors. Instead of furthering the friendship with Poles, Lithuanians turned their backs on them. Now a new vision, entitled “Lithuania 2030,” is focusing on the Nordic-Baltic region.

The Nordic region consists of Scandinavians (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Iceland) and Finland. All five have secure spots in the top 20 of world's most affluent nations, three are deemed extremely competitive economies, and all save Iceland have a reputation of being least corrupt. Joining a company like that does indeed make sense. But is the Nordic direction Lithuania's best option?

Light-years to Scandinavian prosperity and tolerance

One Lithuanian diplomat tells 15min how once, in a bus in Stockholm, he saw a poster showing a map of the Baltic and Nordic countries. All capital cities were properly labelled, except the Lithuanian capital. To his astonished question why it was so, he received the following reply: Vilnius is the only capital not situated on the coast and Lithuanians are the only Catholics in the group.

However, many politicians, diplomats, and political analysts still believe that Lithuania and other Baltic states should move in this direction.

“The most promising space for Lithuania's self-fulfilment is the “Northern Arc”: a dynamic region of sovereign Baltic-Nordic countries, maintaining close ties with the trans-Atlantic partners, Great Britain, and other EU states,” Lithuania's Foreign Minister Audronius Ažubalis explains.

By joining forces with Scandinavians, Lithuania is strengthening its reliability, attractiveness to investors and economic prosperity will come after it becomes the centre of Nordic-Baltic trade, transit, and innovations, he assures.

MP Petras Auštrevičius believes that aspiring to the example of these very successful welfare states is not the worst choice. The Nordic countries have only slightly bigger populations than Lithuania's, so there would not be a “big brother” syndrome. Moreover, there have not been significant conflicts between Balts and Scandinavians, lingering historical complexes, fears or grudges. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, Northern Europeans were the first ones to direct their gaze across the Baltic Sea. Over half of major investors in Lithuania come from the region.

By becoming a link between the Nordic countries and Central-Eastern Europe, Lithuania could turn its rather unfavourable geopolitical position into an advantage. As Giedrius Česnakas of the Political Science and Diplomacy Faculty at Vytautas Magnus University notes, one thing that Lithuanians could learn from northerners is their excellent political culture as well as pragmatism and prudence in dealing with partners.

On the other hand, throughout its history, Lithuania moved back and forth on the West-East axis. The North is a new direction. Scandinavian quality of life and social maturity are incomparably higher. Lithuanians still lag light-years behind in their attitudes towards human rights and social and cultural diversity. What do Lithuanians know about Finland or Norway, the history of these nations, do they speak their languages? The same applies to Sweden or Denmark.

Stings from Warsaw

President Dalia Grybauskaitė has a particularly evil eye on Poland. In May, addressing members of the US Lithuanian community, she shared her thoughts: “We are facing a complicated situation in the public sphere. For some reason certain Polish politicians decided that it would be best for now to have Russia as a friend, while all smaller countries are less important and could temporarily serve as scapegoats. Apparently, that is exactly the role we have been assigned.”

According to the state leader, Lithuania is too small to be heard, but there are interests to present information about it “in a negative light,” while Warsaw is waiting for parliamentary elections in hope that the incoming political powers will be friendlier “allegedly to minorities, but in fact to who-knows-whom.”

Foreign policy experts commented on her words by saying that state leaders should refrain from controversial statements about Poland, otherwise Lithuania risks sliding into a vicious circle of wrangles.

As if it were not enough, Grybauskaitė subsequently announced that she feels like making a pause in certain international relations. The pause still continues.

Emotional ties with Poland

Poland has long been considered Lithuania's strategic partner. Political analyst Vladimiras Laučius says that had there been more tangible achievements – like an agreement on name spelling and bilingual street signs – there could have been more safe-checks to prevent the bilateral relations from hitting the current low. “Powers interested in escalating tensions would not be earning dividends now,” Laučius said in World Lithuanian Youth Conference. “Some say that our strategic partnership with Poland paid off. And suddenly we decide that we are now partners with Scandinavians. What that friendship has given us, no one knows, and time is ticking.”

According to him, it is strange how without any discussions in think tanks or the public, Scandinavia was declared the guiding star and Poland ceased being a friend and strategic partner. “Why? Is it one man's decision?” Laučius wonders. “If everyone just lives with the decision, what a weird democracy and public sphere we have.”

Alvydas Nikžentaitis, historian, recently commented that Lithuania lacks basis to associate with the Nordic countries: “Despite common genetics, there is no common emotion. We have an emotional connection with Poles. And if people feel something for each other, it makes them act together or against each other.”

Balts and not Northerners

“Is history a fate?” political scientist Mindaugas Jurkynas answers a question with a question. “It does not determine the future, only influences it. I haven't heard anyone saying we should dump Poland – she is the one that can dump us.”

Several years ago, he studied about one thousand public pronouncements by presidents, prime ministers, and foreign ministers, coming to the following conclusion: Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia identify themselves as Baltic states, not Nordic states.

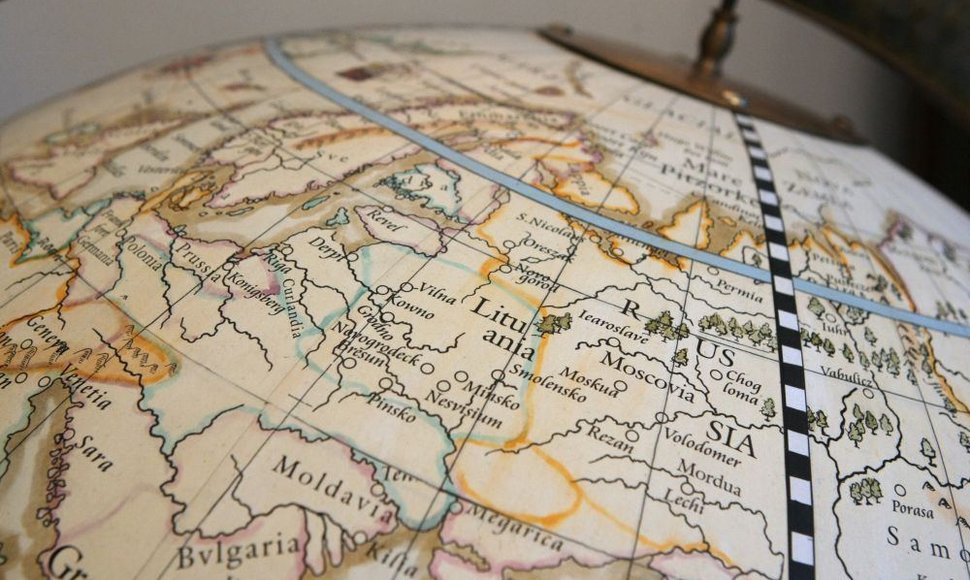

Even though Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves, when he was still the foreign minister, talked about similarities between Estonians and Scandinavians, while Lithuania is often identified with Central Europe, all the three countries have a predominantly Baltic identity. Despite the fact that “the Baltic states” is a recent political coinage that emerged between the two world wars. In fact, back then the term would sometimes accommodate Finland and even Poland.

The public discourse, rhetoric coming from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the president indicates that Lithuania is leaning towards the Nordic countries, yet this direction is not fully exploited, Jurkynas thinks. He says that areas like human rights or social welfare require more work.

“One must live one's own life, not give up one's identity. But there are not many options and we do have close friends [in Scandinavia], we should develop joint projects, further common interests,” Jurkynas says, admitting, though, that “they clearly see us as different.” According to him, there are points of contact with the Nordic countries. For instance, the three monarchs from the House of Vasa who ruled the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Adamkus: “I am still ashamed today”

Lithuania's former president Valdas Adamkus just shrugs when asked to comment on foreign policy changes.

“Relations with Scandinavia have always been great. Over my ten years in office, I've spoken to their officials on all possible topics that today get presented as discovered terra incognita. For instance, it took me and the Swedish Prime Minister an hour and a half in Stockholm to agree on connecting Lithuania and Sweden with an electric cable. Are we inventing a bike today? We've wasted two to four years,” the former president tells 15min.

There have been talks on various topics with Warsaw, too. Adamkus feels vexed that many of the promises he made haven't been kept. He says that the two neighbours are now at the point where Warsaw is dictating the terms and previously cordial but now rather cold ties must be built anew.

“We've had ten years of negotiations, made promises. Many a time it was very difficult for me to look Polish presidents in the face. For instance, my good friend Alexandre Kwasniewski's, whom I assured: It's a done deal in the Seimas [about name spelling], all is settled, there's a vote and we'll solve all misunderstandings with Poles, let's continue to work together. Poland, our strategic partner, voiced everywhere it could: Lithuania must be in the EU, NATO, it's necessary.

“It was similar with late Lech Kaczynski – I made numerous promises to him that misunderstandings in Vilnius would cease, that radical statements were undermining our common interests. That we would somehow solve the name-spelling problem, we would just need to give it to parliamentary vote. Kaczynski is gone and I am still ashamed today that I couldn't keep my promises.”

Previously productive relations are now marred by new rounds of verbal wars. Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski has stated that his country is ready for a new opening in relations with Lithuania, provided it sticks to commitments outlined in bilateral treaty on friendly relations. “And our responsible leaders retort: You are not going to dictate us anything. And tension ensues. So what are we talking about?” Adamkus resents.

Scandinavian pages in Lithuania's history

In 16th and 17th centuries, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was ruled by three kings of the Swedish House of Vasa: Sigismund Vasa (1587-1632), Vladislaus Vasa (1632-1648), and John II Casimir (1648-1668). The latter was faced with a decline of the Republic, wars with Russia and Sweden; he eventually renounced the throne, left for France and joined the Jesuit Order. Claims of Sigismund Vasa, son of Sigismund Augustus' sister Catherine Jagellon, and his heirs to the throne of Sweden sparked a number of clashes with the Polish-Lithuanian state.

During these wars, the grand hetman of the Lithuanian army was Janusz Radziwill, a protestant duke and one of the outstanding personalities of the time, an able politician and military leader, patron of the arts.

Clashing with the powerful Sapieha family, in 1655 in Kėdainiai he and over one thousand other noblemen broke Lithuania's union with Poland and signed a new one with Protestant Sweden. Lithuanians hoped that Sweden would protect their interests and support in war with Russia. The Swedish king, however, saw things differently and the treaty failed to secure the advantages everyone envisaged. Radziwill fell into disfavour of many Lithuanian and Polish noblemen and was even declared a traitor.