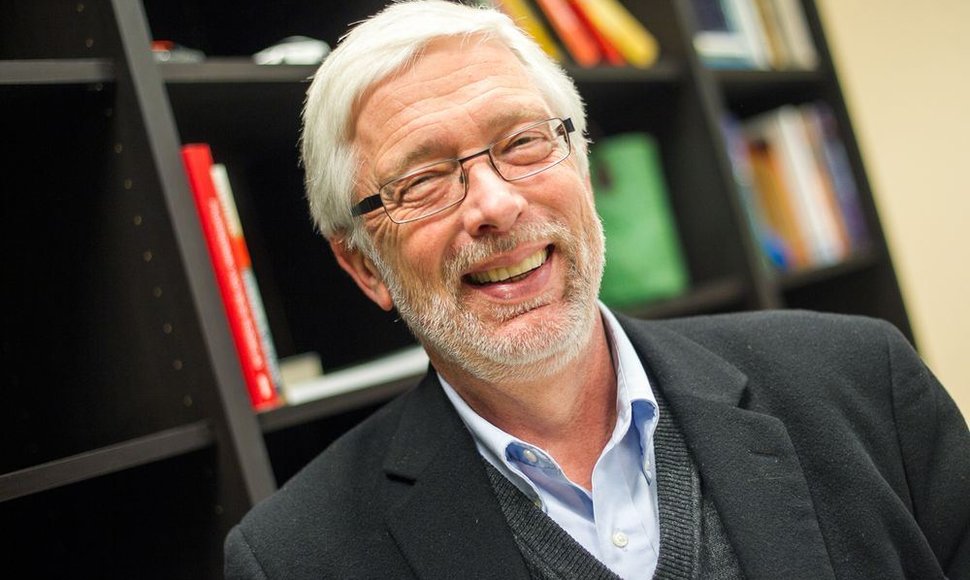

60-year-old Šileika was born in a family of Lithuanian expatriates and, as a child, imagined the land of his parents as a world full of mythical creatures – a strange world, a phantasmagoria, unpredictable but somehow cosy.

“The older I get, the more I write about the world through Lithuanian eyes,” says the author who is presenting the Lithuanian translation of his 2011 novel “Underground.”

– Your parents fled to Canada to escape the approaching Red Army. You were born and raised in Toronto, yet you write about Lithuania. How were you developing your personal relation to a country you'd never known?

– As a child, I imagined Lithuania like a wonderland, a fairy tale. My father would tell me incredible stories with straight face. For example, that my grandmother, his mother, has encountered the devil. He says there was a furnace in the porch of the house.

The grandma is crossing the threshold from the outside and sees the furnace hatch open and a little devil peek out. The grandma makes the sign of the cross and the devil disappears. She goes into the room, opens a door, and again – the devil. Then she splashes the room with holy water – and he is gone. Mystic!

But primitivism of the Lithuanian countryside would often shine through in my father's stories, too. There was never any lamb served in our house. I once tried it as a guest – it was delicious. Back home, I asked: “Why don't we ever eat it?” Father says: “We used to make candles out of lamb fat and the house would smell of sheep all winter.” I was taken aback: “You were so poor? No electricity?” And he: “No, we were advanced. Others would burn cane because they couldn't afford candles.”

Growing in a suburb of Toronto, it was hard for me to grasp what kind of the world my parents were from. I felt captivated listening to them, but at the same time somewhat ashamed.

– How did your parents do in Canada?

– My father was a policeman in Lithuania, so it was hard for him in Canada – he had to work in construction, even though he was already in his 40s. My mum was luckier – she had been a Math and Chemistry teacher and was hired as a narcotics examiner in Canada. True, her dream was to be a housewife – to look after the kids and bake pies. Instead, she had to analyse narcotics.

We, the kids, were impressed by her work. As she was dedicated to her family, she used to tell the police that she must rush home to make dinner. Police cars would escort her home with sirens – for speed. I remember how mother would pull in with a police car, climb out, “Thank you very much,” and go to peel potatoes.

– Your name must have been a giveaway that you weren't local – Antanas. Have you ever had to explain your heritage to your friends?

– I sometimes wonder if a search for identity wasn't what encouraged me to become a writer. Friends used to ask me where my parents were from. Lithuania, I'd say. “Show me on a map,” they'd ask. And there was no such country, Lithuania wasn't on the map back then so no one knew where it was.

I felt as if I came from a non-existent world. Does that mean that I don't exist either? If so, I must create myself. When your name appears in print, then you are, you mean something, you leave a mark. I thought that if I didn't right, I'd simply wouldn't be there anymore.

– What made you write about Lithuanian guerillas to English-speaking audiences? Why would this topic seem relevant to outsiders?

– I always wanted to write about war. At first, I tried to write about war directly, but I failed. Then I thought I'd write about the Holocaust, but I felt I couldn't master the material, it did not belong to me. But I still wanted to say something fresh about the 20th century, about war, about Lithuania.

“Underground” is a book about the tragic, complicated, and profound stories of people in post-war Eastern Europe. I always stress that I'm a novelist, not a historian. That means I use literary techniques to depict certain historical details.

All “Underground” reviews in Canada would start with “this is news for us.” In other words, no one in the West knew about post-war events in Lithuania.

The situation is slowly changing, though, westerners grow increasingly interested in Eastern Europe, they're publishing more fiction about guerillas and resistance in Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania. Fiction becomes a stimulus to look further into the history of Eastern Europe. My novel was very timely. It is intended for readers who are interested in character psychology – and the setting adds an extra intrigue.

– “Underground” tells people's stories that are tragic, complex, profound – nothing to do with the American dream.

– Americans, and most of Westerners, live in a disneyland – a fairytale land where books usually have happy endings. Where the hero strives to achieve the goal and usually succeeds. And if he doesn't, at least the hero learns something important which makes him a better person.

Whereas the Eastern European novel gives a radically different image of the world – it shoes how a person can easily be swept away from the face of the earth, annihilated. That one's freedom of choice can be very limited and consequences dramatic.

For example, in the West, they have this image of a children's author as a kind, gentle, benevolent person. What was Kostas Kubilinskas like? A killer – a children's poet whom the Soviet intelligence made infiltrate into the midst of guerillas, shoot one fighter in sleep, give away their hiding places.

Life is very complex, sometimes all the choice one has is between bad and worse.

– What things are most important for you when you construct a narrative?

– To show that there is a story to tell and the fate of a human being therein. I wished to show that even faced with extreme difficulties, humans remain humans – they love, get tired, want to see their parents, eventually, have a drink and doze off. And, of course, they do not want to die.

When I was looking for prototypes for my characters, I read almost forty books about guerilla resistance in Lithuania. I read many biographies and realized that each guerilla's life is a drama in itself.

I'd often come across the phrase: “We waited to see what would happen next.” It is what a cornered person would say, someone with no room for positive action, forced to hide and wait for who knows what.

I found many a Shakespearean character among guerillas. For example, Lionginas Baliukevičius-Dzūkas is a true Hamlet-type – a melancholic dreamer locked in a bunker. On the one hand, he fears that his parents will be deported to Siberia because of what he does. On the other hand, he cannot act otherwise.

The story of Juozas Lukša-Daumantas is captivating: He flees Lithuania, arrives in Paris, then goes back and dies. Guerillas' biographies are a treasure trove of characters. I had to take all the threads and weave them into a fabric.

– What about your own experiences reflected in the novel? You spent several years in Paris, where you followed your sweetheart Snaigė Valiūnaitė, another Lithuanian who went there to study art. You got married in Paris.

– Paris reappears in my novels often. As a metaphor of free life – Paris means romance, beauty, sweetness of life with a glass of wine. I know this city quite well. When my characters walk down its streets, I know these streets. When they enter a café, I know why they have to stand at a bar and not sit at a table.

– “Underground” is your fourth novel. You published your first one rather late, when you were 41. Did you have to earn a living before you could do what you wanted?

– One cannot make a living on writing books in Canada – that's true. But my writing début got postponed for other reasons – I gave Lithuania its due in my youth.

I took Lithuanian course in Vilnius in 1987. The spirit of independence was already in the air. I realized that was the moment my parents had been speaking about – “One day, Lithuania will need you.”

Between 1987 and 1991, we tried to pressure the Canadian government into recognizing Lithuania's independence. I wrote articles, made appearances on radio and TV, I lived between Lithuania and Canada.

After this turbulent period, I needed time to settle down, to re-enter the more quiet literary work. I published my first novel in 1994.

– Love for Lithuania that your parents nurtured in you is paying dividends – you are a guest of honour in Vilnius Book Fair and you can communicate with your readers without interpreters.

– Keeping a language is much more difficult than it might seem. Language is like a muscle, it needs exercise. I have to learn Lithuanian anew each time – I'm even using different facial muscles to speak Lithuanian and English. After a day, my jaw is sore (laughs).

I always say – English is my tool, but Lithuanian is my melody.

We went to a Lithuanian Saturday school in Toronto, but we weren't a good student: we wouldn't listen in history lessons, be restless all the time, conjugation is still a torture for me, and I get cold sweat each time I think of ū's, ų's, y's, į's.

I used to speak Lithuanian with my parents at the dinner table, but with brothers – English. Among my friends, it is usual to see parents speaking Lithuanian and their kid replying in English. That's how it is.

Lithuanians of my generation do not read Lithuanian books. There's a Lithuanian librarian in one library in Toronto. I once came to take a book about Klaipėda uprising. When do you need it back, I ask. And she says: “Whenever you like, no one else will look for this book.”

– However, your sons, 28-year-old Dainius and 25-year-old Gintaras, do speak Lithuanian. And they are third-generation Canadians.

– Dainius wouldn't even talk to me in English. Something's wrong with us (laughs). To tell you the truth, my wife and I would communicate in English in our young days, but when we had kids, we wanted them to speak the language of their grandparents. It was a struggle – we would tell fairy tales with a dictionary. My son asks me: What is a “titnagas” (flint)? I don't know, I say. He tells me to look it up – and so we learn together.

During our visit to Lithuania in 2004, we took a trip from Nida to Vilnius. My children are reading signs with river names – Še-šu-pė. They look at each other and then go, in unison: “Kur bėga Šešupė, kur Nemunas teka...” (a line from a poem by Lithuanian romantic poet Maironis)

To be honest, we all were quite ironic about Saturday schools, but despite all that, something comes out of it!

– Is it true that you make students at the Humber School for Writers learn how to pronounce your name properly?

– Before college, I was called Tony, but I had a turning-point as a fresher and I became a fanatic – I wouldn't even respond to my friends if they called me anything but Antanas. I also ask my students to pronounce my name properly. I explain them where to put the accent – not AntanAs, but AntAnas.

My son Dainius married a Ukrainian woman. He is moving to Lithuania soon, his dream is to live in Žvėrynas (a neighbourhood in Vilnius). Dainius has studied Eastern European religions, he served in Afghanistan, but in Lithuania, he plans to study linguistics. We'll see how it goes.

– You are coming back to Lithuania with your wife this summer?

– I will come to the Santara-Šviesa convention in Alanta. The emigrant generation of my parents would rally around parishes, while the new generation is united by sports. But I don't care for cepelinai and sports in emigration, but in Santara, they have reviews of modern Lithuanian literature, they hold meetings with authors, publicists, poets, critics. Now that's my cup of tea.

Snaigė will be going to a plain-air in Nida.

Four novels

Lithuanian-Canadian author Antanas Šileika grew up on English and Canadian literature – he works with Canadian literary publications, he still writes reviews and talks about Canadian literature on radio.

Šileika has published four novels: “Dinner at the End of the World” (1994), “Buying on Time” (1997), “Woman in Bronze” (2004, published in Lithuania in 2009), and “Undergorund” (2011). The latter was published in Lithuanian by Versus Aureus last year.

There are plans to turn the novel into a film – production rights have been acquired by Lithuanian director Tomas Donela.