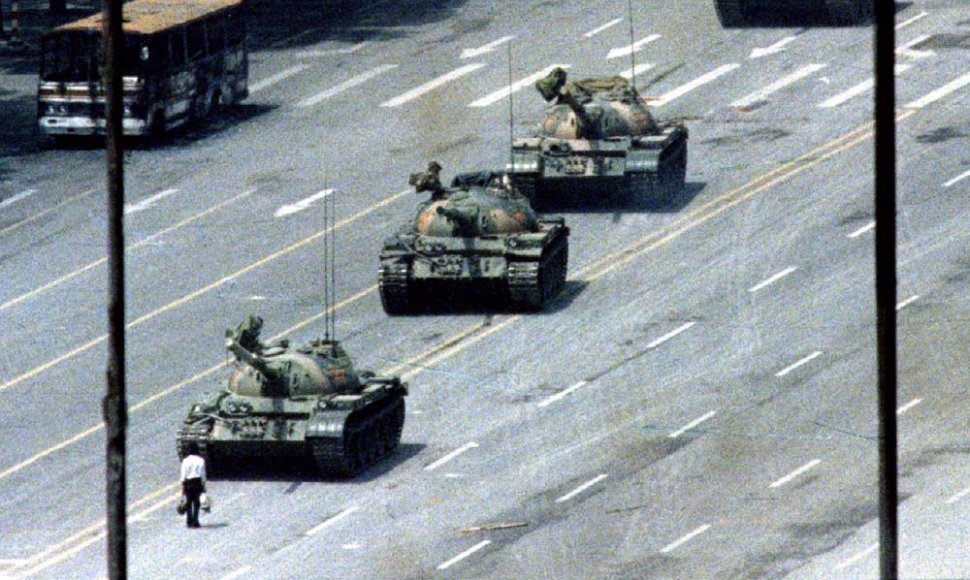

Twenty-four years ago to the day, the student-led pro-democracy movement in Tiananmen Square was brutally suppressed by the Chinese military. Casualties were numerous, though the veil of mystery surrounding the events of June 4, 1989, makes understanding exactly what had occurred a task equally reliant on facts, as much as liberal amounts of guesswork.

The Chinese government is unwilling to disclose the full extent of its knowledge about the incident. This, combined with media censorship in place in China regarding taboo topics such as Tiananmen Square, the underlying assumption is that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) worries about maintaining legitimacy in the eyes of the public by curbing the amount of criticism aimed towards those in power.

Even if the Chinese Communist Party is yet unwilling to discuss its shortcomings in order to enact lasting change, it does not appear that it would be prepared for another confrontation like the one in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

It is much easier to rule a country, when the population is unaware of the negative aspects associated with the government. Whitewashing certain events is useful for maintaining national stability, but comes at the price of restricting human rights and realizing that a government is unable to trust the very people it is sworn to look over. With protests against the government being disallowed (whether in public or online), discourse between those with power and those without it becomes strained, limited and with little possibility of leading to drastic political, social and economic change that would benefit the majority of Chinese citizens.

The questions that must be asked are would another occurrence like that in Tiananmen Square be possible in modern China and does this mean that democratization is impossible to achieve?

Seeing as the Tiananmen Square incident has been officially censored for twenty-four years, it is unlikely that China will see a liberalization of its political mindset in the near future. Essentially, the events of 1989 were a rejection of democratic values and an entrenchment of the Chinese political mindset. Keeping this in mind within the context of the numerous arrests of human rights’ activists within the past decade, it is clear that Beijing’s official stance towards Tiananmen-like incidents is overall negative.

Nonetheless, a similar crackdown would be unlikely to repeat itself: international scrutiny, underground support of pro-democratic movements and the Chinese economy’s dependence on foreign import of goods produced in the Middle Kingdom are all factors meaning that China cannot risk alienating other nations and its own people for the sake of authoritarian-induced stability. Though this is far from democracy and far from maintaining human rights consistently, it is, however, a demonstration of how Beijing has become more aware of its role in the world. Even if the CCP is yet unwilling to discuss its shortcomings in order to enact lasting change, it does not appear that it would be prepared for another confrontation like the one in Tiananmen Square in 1989.